FILM REVIEWS

FILM REVIEWS

Another Woman

Another Woman

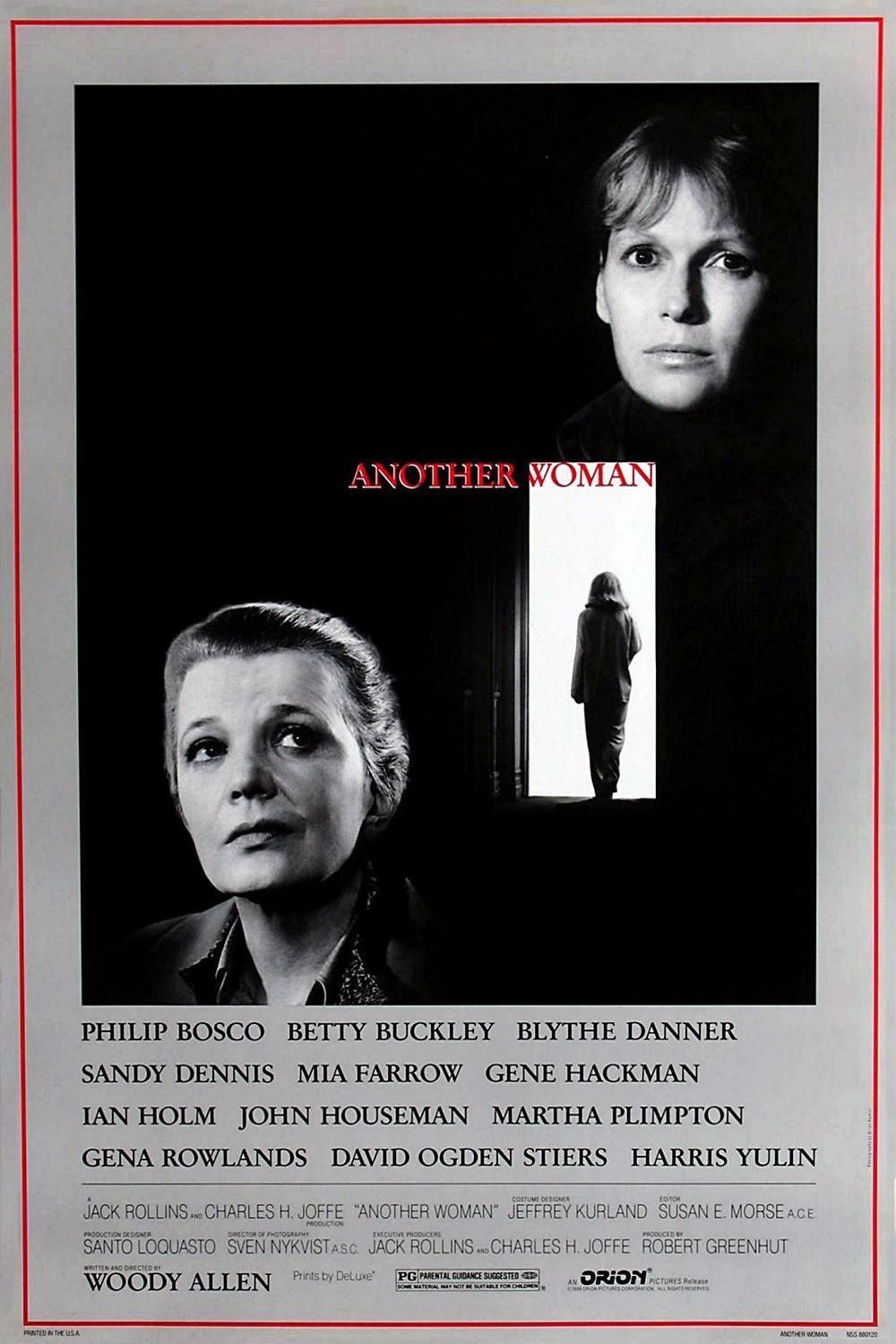

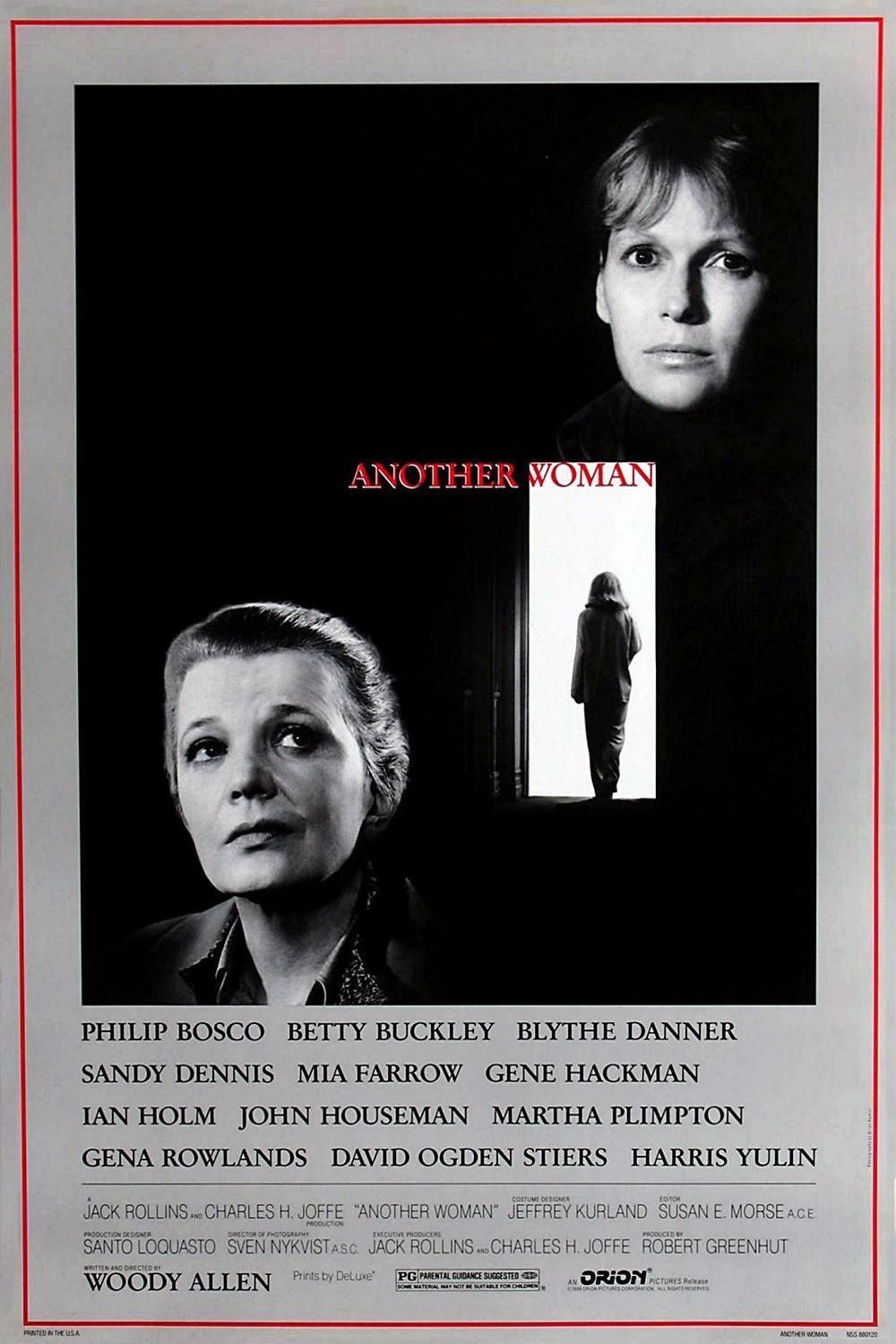

Stills from Another Woman (1988), directed by Woody Allen. © Orion Pictures

Stills from Another Woman (1988), directed by Woody Allen. © Orion Pictures

In 1988, Woody Allen released this film in a dramatic key, once again interrupting the comic tone that characterizes much of his filmography.

In 1988, Woody Allen released this film in a dramatic key, once again interrupting the comic tone that characterizes much of his filmography.

Author

Luciana Trost

Date

November 5, 2025

Share

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the work of Woody Allen, Another Woman brings together the director’s ability to tell simple, everyday stories without losing their power to captivate, drawing on philosophy, literature, music, and psychoanalysis, orientations without which art would be impossible to conceive. The film’s leitmotif is Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, making it difficult not to be moved when this music merges with such a restrained and beautiful story. A drama that stands out in Allen’s filmography, perhaps comparable to Interiors (1978) or September (1987), other gems.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the work of Woody Allen, Another Woman brings together the director’s ability to tell simple, everyday stories without losing their power to captivate, drawing on philosophy, literature, music, and psychoanalysis, orientations without which art would be impossible to conceive. The film’s leitmotif is Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, making it difficult not to be moved when this music merges with such a restrained and beautiful story. A drama that stands out in Allen’s filmography, perhaps comparable to Interiors (1978) or September (1987), other gems.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the work of Woody Allen, Another Woman brings together the director’s ability to tell simple, everyday stories without losing their power to captivate, drawing on philosophy, literature, music, and psychoanalysis, orientations without which art would be impossible to conceive. The film’s leitmotif is Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, making it difficult not to be moved when this music merges with such a restrained and beautiful story. A drama that stands out in Allen’s filmography, perhaps comparable to Interiors (1978) or September (1987), other gems.

Stills from Another Woman (1988), directed by Woody Allen. © Orion Pictures

Stills from Another Woman (1988), directed by Woody Allen. © Orion Pictures

Gena Rowlands stars as Marion Post, a fifty-year-old philosophy professor who teaches at a university and is writing a book on Martin Heidegger. Her personal and professional life appears firmly established. She has a prestigious academic career, her husband is a renowned cardiologist, they maintain an active social life, have many friends, and share a beautiful apartment in New York. Marion’s need for silence and concentration to work on her book leads her to rent a nearby apartment. Her accumulated exhaustion causes her to fall asleep there, only to wake after overhearing a psychoanalysis session from a neighboring office through the ventilation system.

The first session Marion hears is that of a man who longs for the love of another man, regretting that he settled into a marriage with a woman he cares for but does not truly love. As the days pass, the sessions that most capture her attention are those of a pregnant young woman who expresses a persistent dissatisfaction with her life: depression, existential anguish, questions about desire, and long silences. Marion feels deeply drawn to this woman’s words, to the point that we perceive her identification with her and the beginning of a reevaluation of her own life in relation to her marriage, her career, and love. What was not, or what might have been.

Gena Rowlands stars as Marion Post, a fifty-year-old philosophy professor who teaches at a university and is writing a book on Martin Heidegger. Her personal and professional life appears firmly established. She has a prestigious academic career, her husband is a renowned cardiologist, they maintain an active social life, have many friends, and share a beautiful apartment in New York. Marion’s need for silence and concentration to work on her book leads her to rent a nearby apartment. Her accumulated exhaustion causes her to fall asleep there, only to wake after overhearing a psychoanalysis session from a neighboring office through the ventilation system.

The first session Marion hears is that of a man who longs for the love of another man, regretting that he settled into a marriage with a woman he cares for but does not truly love. As the days pass, the sessions that most capture her attention are those of a pregnant young woman who expresses a persistent dissatisfaction with her life: depression, existential anguish, questions about desire, and long silences. Marion feels deeply drawn to this woman’s words, to the point that we perceive her identification with her and the beginning of a reevaluation of her own life in relation to her marriage, her career, and love. What was not, or what might have been.

Gena Rowlands stars as Marion Post, a fifty-year-old philosophy professor who teaches at a university and is writing a book on Martin Heidegger. Her personal and professional life appears firmly established. She has a prestigious academic career, her husband is a renowned cardiologist, they maintain an active social life, have many friends, and share a beautiful apartment in New York. Marion’s need for silence and concentration to work on her book leads her to rent a nearby apartment. Her accumulated exhaustion causes her to fall asleep there, only to wake after overhearing a psychoanalysis session from a neighboring office through the ventilation system.

The first session Marion hears is that of a man who longs for the love of another man, regretting that he settled into a marriage with a woman he cares for but does not truly love. As the days pass, the sessions that most capture her attention are those of a pregnant young woman who expresses a persistent dissatisfaction with her life: depression, existential anguish, questions about desire, and long silences. Marion feels deeply drawn to this woman’s words, to the point that we perceive her identification with her and the beginning of a reevaluation of her own life in relation to her marriage, her career, and love. What was not, or what might have been.

This film stands as one of Woody Allen’s few dramatic films, which, along with September (1987) and Interiors (1978), form part of the director’s exquisite and lesser-explored catalog.

This film stands as one of Woody Allen’s few dramatic films, which, along with September (1987) and Interiors (1978), form part of the director’s exquisite and lesser-explored catalog.

This film stands as one of Woody Allen’s few dramatic films, which, along with September (1987) and Interiors (1978), form part of the director’s exquisite and lesser-explored catalog.

“I need something, I just don’t know exactly what,” Marion tells her brother during a visit to his workplace. The film disrupts its apparent harmony with memories and dreamlike visions that prove decisive. We see childhood memories of a strict father who admired her but not her brother, who resisted the family’s expectations; a scene in a theater where Marion watches dramatized moments from her own life, including her youth married to a university professor from whom she became pregnant and chose to have an abortion; and her current relationship with her husband, marked by a routine in which intimacy barely exists.

The intertwining of Marion’s personal history with her growing fascination for the pregnant young woman becomes increasingly intense. By chance, or perhaps not, she encounters her in an antique shop, crying in front of Gustav Klimt’s painting Hope. A shared lunch brings them closer, and it is here that Marion finally begins to understand.

“I need something, I just don’t know exactly what,” Marion tells her brother during a visit to his workplace. The film disrupts its apparent harmony with memories and dreamlike visions that prove decisive. We see childhood memories of a strict father who admired her but not her brother, who resisted the family’s expectations; a scene in a theater where Marion watches dramatized moments from her own life, including her youth married to a university professor from whom she became pregnant and chose to have an abortion; and her current relationship with her husband, marked by a routine in which intimacy barely exists.

The intertwining of Marion’s personal history with her growing fascination for the pregnant young woman becomes increasingly intense. By chance, or perhaps not, she encounters her in an antique shop, crying in front of Gustav Klimt’s painting Hope. A shared lunch brings them closer, and it is here that Marion finally begins to understand.

“I need something, I just don’t know exactly what,” Marion tells her brother during a visit to his workplace. The film disrupts its apparent harmony with memories and dreamlike visions that prove decisive. We see childhood memories of a strict father who admired her but not her brother, who resisted the family’s expectations; a scene in a theater where Marion watches dramatized moments from her own life, including her youth married to a university professor from whom she became pregnant and chose to have an abortion; and her current relationship with her husband, marked by a routine in which intimacy barely exists.

The intertwining of Marion’s personal history with her growing fascination for the pregnant young woman becomes increasingly intense. By chance, or perhaps not, she encounters her in an antique shop, crying in front of Gustav Klimt’s painting Hope. A shared lunch brings them closer, and it is here that Marion finally begins to understand.

Stills from Another Woman (1988), directed by Woody Allen. © Orion Pictures

Stills from Another Woman (1988), directed by Woody Allen. © Orion Pictures

Explore Topics

Marion mentions two poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, her mother’s favorite poet. One of them stands out:

Archaic Torso of Apollo

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so,

nor could a smile run through the placid hips

and thighs to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur;

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Marion mentions two poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, her mother’s favorite poet. One of them stands out:

Archaic Torso of Apollo

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so,

nor could a smile run through the placid hips

and thighs to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur;

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Film credits

Original title

Another Woman

Year

1988

COUNTRY

United States

Director

Woody Allen

Screenplay

Woody Allen

Cast

Gena Rowlands, Gene Hackman, Mia Farrow, Ian Holm, Blythe Danner, Martha Plimpton, Josh Hamilton, Frances Conroy, Betty Buckley, John Houseman, Sandy Dennis, David Ogden Stiers

Music

Various

Cinematography

Sven Nykvist

Production companies

Jack Rollins & Charles H. Joffe Production

Distributor

Orion Pictures

Genre

Drama | Psychological Drama

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

Poor Things: Opening Minds

Poor Things: Opening Minds

Poor Things: Opening Minds

director

Yorgos Lanthimos

country

Ireland

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

director

Wim Wenders

country

Japan

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

director

Luis Ortega

country

Argentina

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.