FILM REVIEWS

FILM REVIEWS

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

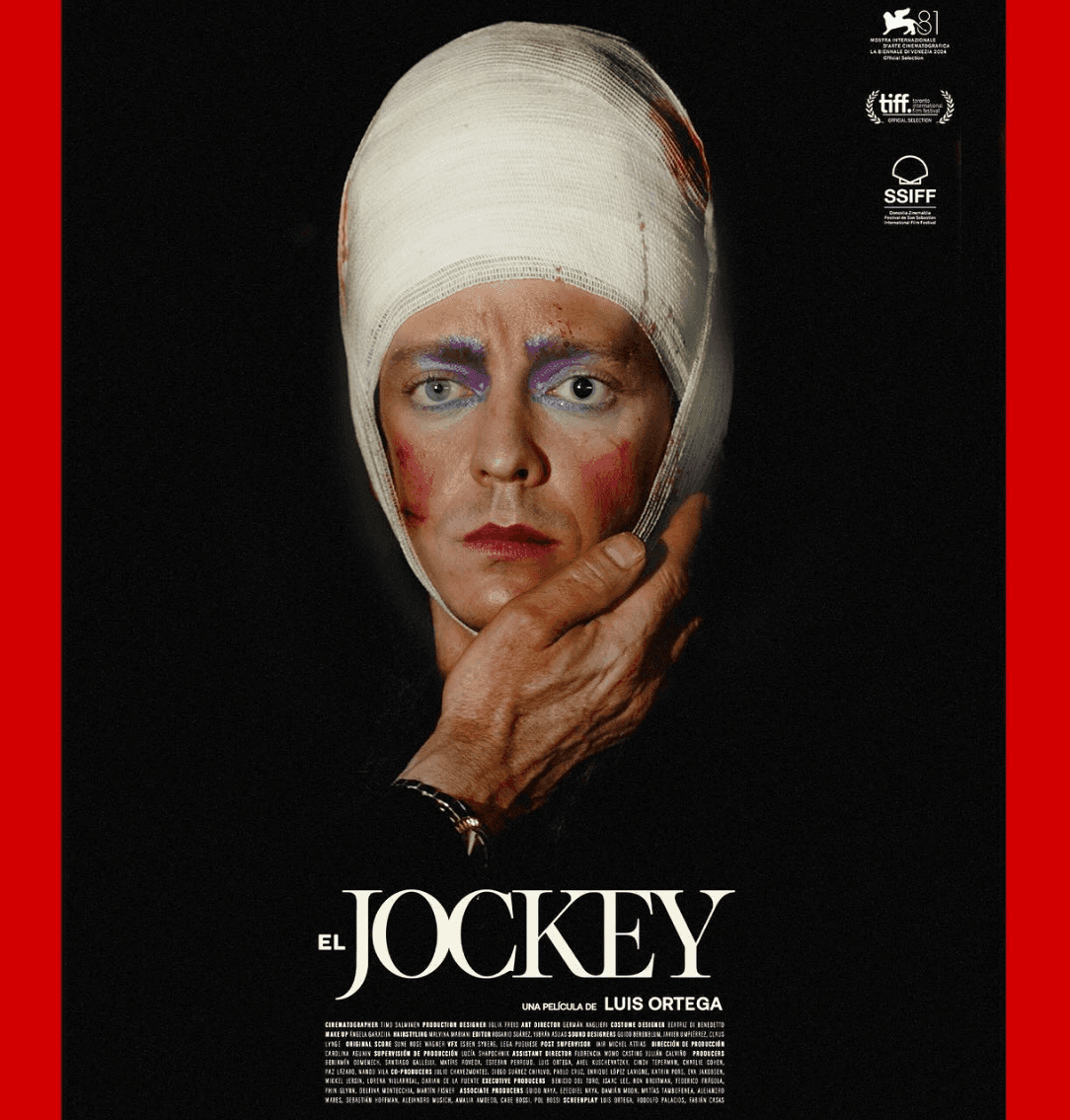

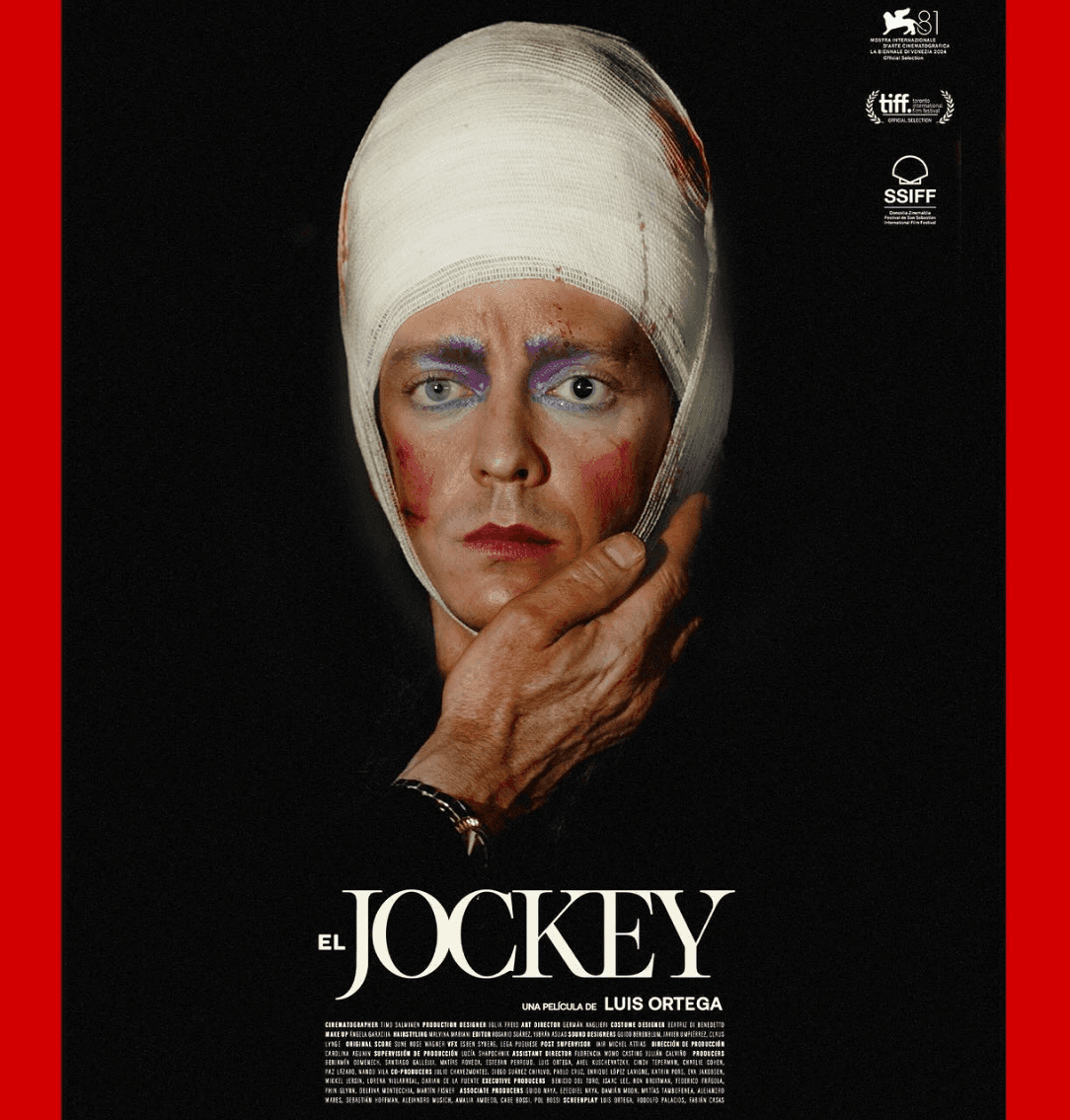

STILLS FROM EL JOCKEY (2024), DIRECTED BY LUIS ORTEGA.

© CARAMEL FILMS.

STILLS FROM EL JOCKEY (2024), DIRECTED BY LUIS ORTEGA.

© CARAMEL FILMS.

Once again, Luis Ortega bursts onto the cinematic scene with a proposal for a different kind of film, delving into problems that concern the human condition through characters and settings that border on marginality.

Once again, Luis Ortega bursts onto the cinematic scene with a proposal for a different kind of film, delving into problems that concern the human condition through characters and settings that border on marginality.

Author

Luciana Trost

Date

November 14, 2025

Share

From a philosophical perspective, El Jockey (2024), distributed by Star Distribution Latin America and awarded Best Latin American Film at the San Sebastián International Film Festival, raises questions about being and, more explicitly within the film, about identity. Ortega has already accustomed us, and yet never ceases to surprise us, to profound themes treated through films that break away from the pre-chewed tradition of cinema, allowing viewers to question life, death, love, hatred, weariness, otherness, and the postmodern world.

From a philosophical perspective, El Jockey (2024), distributed by Star Distribution Latin America and awarded Best Latin American Film at the San Sebastián International Film Festival, raises questions about being and, more explicitly within the film, about identity. Ortega has already accustomed us, and yet never ceases to surprise us, to profound themes treated through films that break away from the pre-chewed tradition of cinema, allowing viewers to question life, death, love, hatred, weariness, otherness, and the postmodern world.

From a philosophical perspective, El Jockey (2024), distributed by Star Distribution Latin America and awarded Best Latin American Film at the San Sebastián International Film Festival, raises questions about being and, more explicitly within the film, about identity. Ortega has already accustomed us, and yet never ceases to surprise us, to profound themes treated through films that break away from the pre-chewed tradition of cinema, allowing viewers to question life, death, love, hatred, weariness, otherness, and the postmodern world.

STILLS FROM EL JOCKEY (2024), DIRECTED BY LUIS ORTEGA.

© CARAMEL FILMS.

STILLS FROM EL JOCKEY (2024), DIRECTED BY LUIS ORTEGA.

© CARAMEL FILMS.

El Jockey brings us closer to a disruptive, frenetic, dreamlike, and at the same time profoundly real form of cinema, something rarely found on commercial screens. Remo Manfredi, played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, the jockey and main character, faces an existential crisis regarding his career as a professional rider. After countless victories, trophies, and exorbitant earnings for his superiors or bosses, a true mafia-like and aristocratic refuge of the elite within the world of jockeying and gambling, the only way he feels capable of continuing in that environment is through the use and abuse of drugs and alcohol. In other words, by covering up his anguish. His refuge from this depression and from the exhaustion of a monotonous, material life is his girlfriend, another jockey named Abril, played by Úrsula Corberó, who has a promising future ahead of her and whom Remo loves deeply.

El Jockey brings us closer to a disruptive, frenetic, dreamlike, and at the same time profoundly real form of cinema, something rarely found on commercial screens. Remo Manfredi, played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, the jockey and main character, faces an existential crisis regarding his career as a professional rider. After countless victories, trophies, and exorbitant earnings for his superiors or bosses, a true mafia-like and aristocratic refuge of the elite within the world of jockeying and gambling, the only way he feels capable of continuing in that environment is through the use and abuse of drugs and alcohol. In other words, by covering up his anguish. His refuge from this depression and from the exhaustion of a monotonous, material life is his girlfriend, another jockey named Abril, played by Úrsula Corberó, who has a promising future ahead of her and whom Remo loves deeply.

El Jockey brings us closer to a disruptive, frenetic, dreamlike, and at the same time profoundly real form of cinema, something rarely found on commercial screens. Remo Manfredi, played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, the jockey and main character, faces an existential crisis regarding his career as a professional rider. After countless victories, trophies, and exorbitant earnings for his superiors or bosses, a true mafia-like and aristocratic refuge of the elite within the world of jockeying and gambling, the only way he feels capable of continuing in that environment is through the use and abuse of drugs and alcohol. In other words, by covering up his anguish. His refuge from this depression and from the exhaustion of a monotonous, material life is his girlfriend, another jockey named Abril, played by Úrsula Corberó, who has a promising future ahead of her and whom Remo loves deeply.

Ortega has already accustomed us to profound themes treated through films that break away from the pre-chewed tradition of cinema.

Ortega has already accustomed us to profound themes treated through films that break away from the pre-chewed tradition of cinema.

Ortega has already accustomed us to profound themes treated through films that break away from the pre-chewed tradition of cinema.

Yet addiction ultimately leads him to ruin. A terrible accident during a race with his new horse, imported from Japan and valued at a million dollars, leaves him hospitalized with a fatal prognosis. This is where the film introduces a decisive turning point. Remo miraculously and unexpectedly awakens and leaves the hospital dressed in the clothes of a woman who, also hospitalized, had occupied the bed next to his. His strange behavior unfolds without pause. He wanders the streets wearing makeup, sees his reflection in a mirror only for it to vanish without rational explanation, steps onto a pharmacy scale and finds that his weight is zero. The notion of body weight, a metaphor for the weight of being and existence, had already appeared at the beginning of the film, when riders are required to weigh in before a race.

Yet addiction ultimately leads him to ruin. A terrible accident during a race with his new horse, imported from Japan and valued at a million dollars, leaves him hospitalized with a fatal prognosis. This is where the film introduces a decisive turning point. Remo miraculously and unexpectedly awakens and leaves the hospital dressed in the clothes of a woman who, also hospitalized, had occupied the bed next to his. His strange behavior unfolds without pause. He wanders the streets wearing makeup, sees his reflection in a mirror only for it to vanish without rational explanation, steps onto a pharmacy scale and finds that his weight is zero. The notion of body weight, a metaphor for the weight of being and existence, had already appeared at the beginning of the film, when riders are required to weigh in before a race.

Yet addiction ultimately leads him to ruin. A terrible accident during a race with his new horse, imported from Japan and valued at a million dollars, leaves him hospitalized with a fatal prognosis. This is where the film introduces a decisive turning point. Remo miraculously and unexpectedly awakens and leaves the hospital dressed in the clothes of a woman who, also hospitalized, had occupied the bed next to his. His strange behavior unfolds without pause. He wanders the streets wearing makeup, sees his reflection in a mirror only for it to vanish without rational explanation, steps onto a pharmacy scale and finds that his weight is zero. The notion of body weight, a metaphor for the weight of being and existence, had already appeared at the beginning of the film, when riders are required to weigh in before a race.

STILLS FROM EL JOCKEY (2024), DIRECTED BY LUIS ORTEGA.

© CARAMEL FILMS.

Explore Topics

And ontological questions begin to arise in the character (...): Who am I? Am I the same one who raced? Am I him, or a new person? Or am I both?

And ontological questions begin to arise in the character (...): Who am I? Am I the same one who raced? Am I him, or a new person? Or am I both?

And ontological questions begin to arise in the character (...): Who am I? Am I the same one who raced? Am I him, or a new person? Or am I both?

At this point, the viewer may recall Remo asking Abril, “What do I have to do for you to keep loving me?” to which she responds, “Die and be born again.” Something of this seems to take shape throughout the rest of the film. A death and a resurrection for Manfredi, and also for Abril. Ontological questions begin to arise in the character, and extend to others as well. Who am I? Am I the same one who raced? Am I him, or a new person? Or am I both? In his wandering through the streets, searching for something we do not fully know, recalling figures from the French Nouvelle Vague, Remo commits several crimes that lead him to prison, where he becomes her, or at least an other, unleashing dreamlike and irrational scenes.

The film’s musical atmosphere is exquisite, merging dance and music, two essential languages at its core. The soundtrack draws mostly from Argentine songs of the 1960s and 1980s: “Fumemos un cigarrillo” by Piero, “Lo mismo que a Usted” (Palito Ortega), “Trigal” (Sandro), and “Sin Disfraz” (Virus), the latter as part of the film’s opening climax. Particularly noteworthy is the first verse of that song, which pierces the heart of the film: A veces voy donde reina el mar. Es mi lugar llego sin disfraz. Por un minuto abandono el frac. Y me descubro en lo espiritual, ara amar. Como si fuera mentiroso y nudista. En taxi voy hotel Savoy y bailamos. Y ya no se si es hoy, ayer o mañana. (1)

Martin Heidegger states in the opening pages of Being and Time (1927) that every question about being is already a search. Since the film approaches these philosophical issues of being and identity with humorous, dramatic, and even grotesque overtones, as viewers we are compelled to continue asking questions in order to arrive at open-ended answers, even if this may sound like an oxymoron.

At this point, the viewer may recall Remo asking Abril, “What do I have to do for you to keep loving me?” to which she responds, “Die and be born again.” Something of this seems to take shape throughout the rest of the film. A death and a resurrection for Manfredi, and also for Abril. Ontological questions begin to arise in the character, and extend to others as well. Who am I? Am I the same one who raced? Am I him, or a new person? Or am I both? In his wandering through the streets, searching for something we do not fully know, recalling figures from the French Nouvelle Vague, Remo commits several crimes that lead him to prison, where he becomes her, or at least an other, unleashing dreamlike and irrational scenes.

The film’s musical atmosphere is exquisite, merging dance and music, two essential languages at its core. The soundtrack draws mostly from Argentine songs of the 1960s and 1980s: “Fumemos un cigarrillo” by Piero, “Lo mismo que a Usted” (Palito Ortega), “Trigal” (Sandro), and “Sin Disfraz” (Virus), the latter as part of the film’s opening climax. Particularly noteworthy is the first verse of that song, which pierces the heart of the film: A veces voy donde reina el mar. Es mi lugar llego sin disfraz. Por un minuto abandono el frac. Y me descubro en lo espiritual, ara amar. Como si fuera mentiroso y nudista. En taxi voy hotel Savoy y bailamos. Y ya no se si es hoy, ayer o mañana. (1)

Martin Heidegger states in the opening pages of Being and Time (1927) that every question about being is already a search. Since the film approaches these philosophical issues of being and identity with humorous, dramatic, and even grotesque overtones, as viewers we are compelled to continue asking questions in order to arrive at open-ended answers, even if this may sound like an oxymoron.

(1) Sometimes I go where the sea rules.

It is my place, I arrive with no disguise.

For a minute I leave the tailcoat behind.

And I find myself in the spiritual, to love.

As if I were deceitful and a nudist.

By taxi I go to the Savoy Hotel and we dance.

And I no longer know if it is today, yesterday or tomorrow.

(1) Sometimes I go where the sea rules.

It is my place, I arrive with no disguise.

For a minute I leave the tailcoat behind.

And I find myself in the spiritual, to love.

As if I were deceitful and a nudist.

By taxi I go to the Savoy Hotel and we dance.

And I no longer know if it is today, yesterday or tomorrow.

(1) Sometimes I go where the sea rules.

It is my place, I arrive with no disguise.

For a minute I leave the tailcoat behind.

And I find myself in the spiritual, to love.

As if I were deceitful and a nudist.

By taxi I go to the Savoy Hotel and we dance.

And I no longer know if it is today, yesterday or tomorrow.

Film credits

Original title

El Jockey

Year

2024

COUNTRY

Argentina

Director

Luis Ortega

Screenplay

Luis Ortega, Fabián Casas, Rodolfo Palacios

Cast

Nahuel Pérez Biscayart, Úrsula Corberó, Daniel Giménez Cacho, Mariana Di Girolamo, Daniel Fanego, Osmar Nuñez, Luis Ziembrowski, Roberto Carnaghi, Adriana Aguirre, Roly Serrano

Music

Sune Wagner

Cinematography

Timo Salminen

Production companies

Argentina–Mexico–Spain–Denmark–United States co-production; Rei Cine, El Despacho Produkties, Infinity Hill, Exile Content Studio, Warner Music

Distributor

Caramel Films

Genre

Cinema, Drama, Sci-Fi

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

Poor Things: Opening Minds

Poor Things: Opening Minds

Poor Things: Opening Minds

director

Yorgos Lanthimos

country

Ireland

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

director

Wim Wenders

country

Japan

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

director

Luis Ortega

country

Argentina

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.