FILM REVIEWS

FILM REVIEWS

Fort-Da and the Void of Chinese Philosophy in Paterson

Fort-Da and the Void of Chinese Philosophy in Paterson

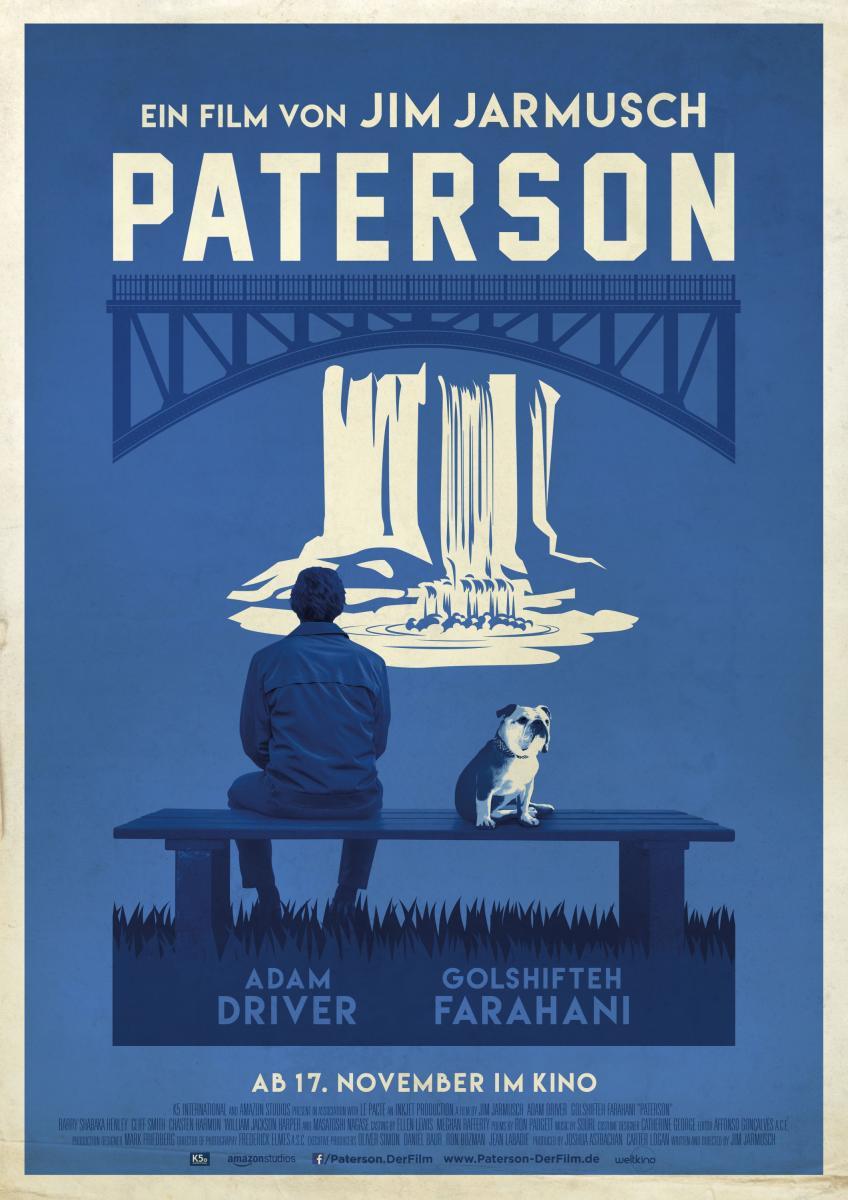

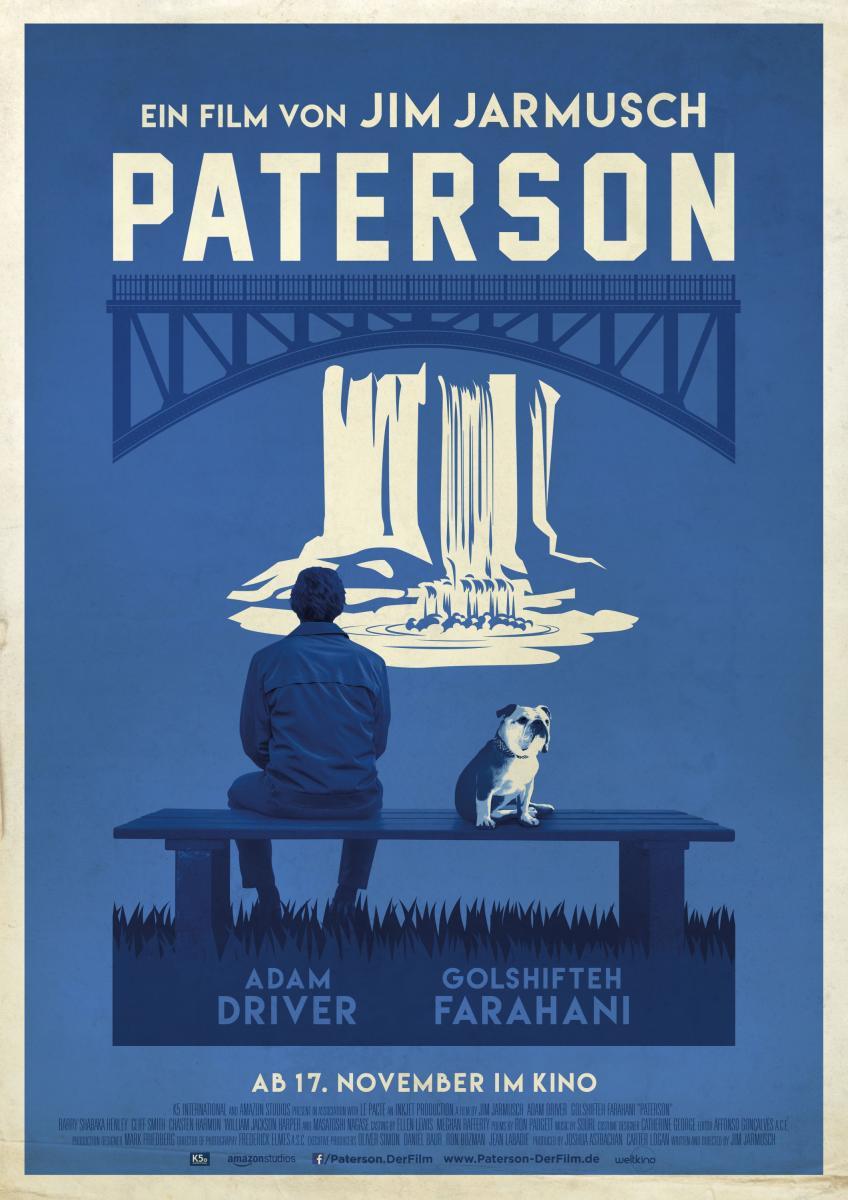

Stills from Paterson (2016), directed by Jim Jarmusch.

© Amazon Studios

Stills from Paterson (2016), directed by Jim Jarmusch.

© Amazon Studios

Jarmusch’s sharp and sensitive eye offers a beautiful audiovisual work set in a quiet American town, whose protagonist leads us to reflect on notions such as fort da, the void and thirdness in psychoanalysis.

Jarmusch’s sharp and sensitive eye offers a beautiful audiovisual work set in a quiet American town, whose protagonist leads us to reflect on notions such as fort da, the void and thirdness in psychoanalysis.

Author

Luciana Trost

Date

September 28, 2025

Share

This text, which we note in advance contains spoilers, seeks to analyze the film Paterson (2016) through several themes linked to psychoanalysis and Chinese philosophy, including the notion of fort da and the void. We will focus on what we consider a turning point in the film: Paterson’s loss of the notebook containing his poems. It is therefore relevant to examine that event through Freud’s concept of the Fort Da game, later discussed by the essayist Didi Huberman, as well as Françoise Cheng’s idea of the void in Chinese philosophy and art. We will also draw on the concept of Thirdness, developed by Peirce and later taken up by Freud, and on the dissolution of the Oedipus Complex, which we consider important for understanding this moment in the film. From that point on, Paterson becomes aware of what he had: his notebook of poems. The loss of that object, which seems to have stirred something in him, generates an absence that can give rise to a certain alterity, to thirdness, to the emergence of something else, something new, unexpected and contingent, outside his routine world. In this sense, the absence of the notebook functions as a regulator of Paterson’s behavior.

This text, which we note in advance contains spoilers, seeks to analyze the film Paterson (2016) through several themes linked to psychoanalysis and Chinese philosophy, including the notion of fort da and the void. We will focus on what we consider a turning point in the film: Paterson’s loss of the notebook containing his poems. It is therefore relevant to examine that event through Freud’s concept of the Fort Da game, later discussed by the essayist Didi Huberman, as well as Françoise Cheng’s idea of the void in Chinese philosophy and art. We will also draw on the concept of Thirdness, developed by Peirce and later taken up by Freud, and on the dissolution of the Oedipus Complex, which we consider important for understanding this moment in the film. From that point on, Paterson becomes aware of what he had: his notebook of poems. The loss of that object, which seems to have stirred something in him, generates an absence that can give rise to a certain alterity, to thirdness, to the emergence of something else, something new, unexpected and contingent, outside his routine world. In this sense, the absence of the notebook functions as a regulator of Paterson’s behavior.

This text, which we note in advance contains spoilers, seeks to analyze the film Paterson (2016) through several themes linked to psychoanalysis and Chinese philosophy, including the notion of fort da and the void. We will focus on what we consider a turning point in the film: Paterson’s loss of the notebook containing his poems. It is therefore relevant to examine that event through Freud’s concept of the Fort Da game, later discussed by the essayist Didi Huberman, as well as Françoise Cheng’s idea of the void in Chinese philosophy and art. We will also draw on the concept of Thirdness, developed by Peirce and later taken up by Freud, and on the dissolution of the Oedipus Complex, which we consider important for understanding this moment in the film. From that point on, Paterson becomes aware of what he had: his notebook of poems. The loss of that object, which seems to have stirred something in him, generates an absence that can give rise to a certain alterity, to thirdness, to the emergence of something else, something new, unexpected and contingent, outside his routine world. In this sense, the absence of the notebook functions as a regulator of Paterson’s behavior.

Stills from Paterson (2016), directed by Jim Jarmusch.

© Amazon Studios

Stills from Paterson (2016), directed by Jim Jarmusch.

© Amazon Studios

Paterson is not only the name of the film’s protagonist but also the name of the New Jersey city where the story unfolds and the title of the epic poem by William Carlos Williams, who is referenced throughout the film. Paterson works as a bus driver who travels through the city while writing poetry in a notebook. His life is routine, yet this does not seem to trouble him. Poetry appears to be the medium that frees him from the idea of a monotonous, dull existence. He lives with his wife Laura and their bulldog Marvin. On workdays he wakes up at the same time every morning without an alarm, as if something within him rouses him without external stimuli. He drives through the city observing and listening to the behavior of his passengers or of those he sees through the windshield.

Paterson is not only the name of the film’s protagonist but also the name of the New Jersey city where the story unfolds and the title of the epic poem by William Carlos Williams, who is referenced throughout the film. Paterson works as a bus driver who travels through the city while writing poetry in a notebook. His life is routine, yet this does not seem to trouble him. Poetry appears to be the medium that frees him from the idea of a monotonous, dull existence. He lives with his wife Laura and their bulldog Marvin. On workdays he wakes up at the same time every morning without an alarm, as if something within him rouses him without external stimuli. He drives through the city observing and listening to the behavior of his passengers or of those he sees through the windshield.

Paterson is not only the name of the film’s protagonist but also the name of the New Jersey city where the story unfolds and the title of the epic poem by William Carlos Williams, who is referenced throughout the film. Paterson works as a bus driver who travels through the city while writing poetry in a notebook. His life is routine, yet this does not seem to trouble him. Poetry appears to be the medium that frees him from the idea of a monotonous, dull existence. He lives with his wife Laura and their bulldog Marvin. On workdays he wakes up at the same time every morning without an alarm, as if something within him rouses him without external stimuli. He drives through the city observing and listening to the behavior of his passengers or of those he sees through the windshield.

This text aims to analyze "Paterson" through several themes tied to psychoanalysis and Chinese philosophy, including the notion of fort da and the void.

This text aims to analyze "Paterson" through several themes tied to psychoanalysis and Chinese philosophy, including the notion of fort da and the void.

This text aims to analyze "Paterson" through several themes tied to psychoanalysis and Chinese philosophy, including the notion of fort da and the void.

Laura insists that he should publish his poems because she believes the world should know their beauty. He listens to her but does not seem to agree. He also promises to make a backup copy. Days pass, Paterson does not make the copy and Marvin destroys the notebook, leaving no trace of the poems. This is the first time we see Paterson truly distressed, even if he does not show it openly. His emotions seem to flow more naturally through writing. Following this event, during a walk that leads him to a small park with a waterfall, Paterson sits on a bench and is soon joined by a Japanese man who takes out Paterson, the book of poems by William Carlos Williams, whom Paterson admires. Noticing his gaze, the man starts a conversation, comments on the poetic nature of being a bus driver in the city of Paterson and after a silence gives him a notebook with blank pages as a gift. He tells him that sometimes empty pages offer more possibilities.

Freud introduces this concept in Beyond the Pleasure Principle while observing his eighteen month old grandson, who would throw a spool of thread away from his crib while uttering a prolonged “Ohhh” (Fort, it is gone) and then, when it reappeared, joyfully exclaim “Da” (“There, there it is”). The oscillation between “far away absent” and “there present” represents the necessary force of alterity that allows for imaginary identification. The spool only lives when it appears to the child, while it returns to the inanimate or dies when it disappears. This can be understood as an allusion to a game of mourning, showing that life is possible only in alternation with death.

Laura insists that he should publish his poems because she believes the world should know their beauty. He listens to her but does not seem to agree. He also promises to make a backup copy. Days pass, Paterson does not make the copy and Marvin destroys the notebook, leaving no trace of the poems. This is the first time we see Paterson truly distressed, even if he does not show it openly. His emotions seem to flow more naturally through writing. Following this event, during a walk that leads him to a small park with a waterfall, Paterson sits on a bench and is soon joined by a Japanese man who takes out Paterson, the book of poems by William Carlos Williams, whom Paterson admires. Noticing his gaze, the man starts a conversation, comments on the poetic nature of being a bus driver in the city of Paterson and after a silence gives him a notebook with blank pages as a gift. He tells him that sometimes empty pages offer more possibilities.

Freud introduces this concept in Beyond the Pleasure Principle while observing his eighteen month old grandson, who would throw a spool of thread away from his crib while uttering a prolonged “Ohhh” (Fort, it is gone) and then, when it reappeared, joyfully exclaim “Da” (“There, there it is”). The oscillation between “far away absent” and “there present” represents the necessary force of alterity that allows for imaginary identification. The spool only lives when it appears to the child, while it returns to the inanimate or dies when it disappears. This can be understood as an allusion to a game of mourning, showing that life is possible only in alternation with death.

Laura insists that he should publish his poems because she believes the world should know their beauty. He listens to her but does not seem to agree. He also promises to make a backup copy. Days pass, Paterson does not make the copy and Marvin destroys the notebook, leaving no trace of the poems. This is the first time we see Paterson truly distressed, even if he does not show it openly. His emotions seem to flow more naturally through writing. Following this event, during a walk that leads him to a small park with a waterfall, Paterson sits on a bench and is soon joined by a Japanese man who takes out Paterson, the book of poems by William Carlos Williams, whom Paterson admires. Noticing his gaze, the man starts a conversation, comments on the poetic nature of being a bus driver in the city of Paterson and after a silence gives him a notebook with blank pages as a gift. He tells him that sometimes empty pages offer more possibilities.

Freud introduces this concept in Beyond the Pleasure Principle while observing his eighteen month old grandson, who would throw a spool of thread away from his crib while uttering a prolonged “Ohhh” (Fort, it is gone) and then, when it reappeared, joyfully exclaim “Da” (“There, there it is”). The oscillation between “far away absent” and “there present” represents the necessary force of alterity that allows for imaginary identification. The spool only lives when it appears to the child, while it returns to the inanimate or dies when it disappears. This can be understood as an allusion to a game of mourning, showing that life is possible only in alternation with death.

Stills from Paterson (2016), directed by Jim Jarmusch.

© Amazon Studios

Explore Topics

From the moment Paterson loses his poems, he becomes aware of his loss and alterity emerges, breaking the monotony of his life.

From the moment Paterson loses his poems, he becomes aware of his loss and alterity emerges, breaking the monotony of his life.

From the moment Paterson loses his poems, he becomes aware of his loss and alterity emerges, breaking the monotony of his life.

We know that Paterson struggles to express his emotions but manages to channel them through poetry. It is the way he opens himself to the world. Until he loses his notebook, the entire film unfolds in a monotonous state of pure presence or pure Da. We see this not only in the fact that Paterson writes his poems without acknowledging their importance, in contrast to Laura, who perceives their beauty and the need for him to share them. Paterson seems to inhabit a state of complete fullness. His routine on the way to work is the same, his routine at home is the same and his writing routine in the notebook is the same.

It is not until his dog destroys the notebook and leaves no trace of the poems that Paterson becomes aware of his loss, Fort. At that moment alterity or thirdness emerges, breaking the monotony of his life. This alterity also relates to Cheng’s notion of the void and to Peirce’s thirdness, brought back by Freud, in the sense that the structure of his life is disrupted and something linked to Law appears. His understanding of the world expands with this loss, just as the child at the end of the Oedipus Complex realizes that life is no longer binary, mother and child, but organized around a third term, the Father or Law, which will regulate life from that moment on and make relations with the world possible. This produced and necessary void is embodied in the empty notebook given to Paterson when the stranger notices, without many words, that he is an avid reader of poetry. It seems then that this void brings with it the thirdness or Law that is needed and that, as we noted, may well be represented by the Japanese man who gives Paterson the notebook. It opens the way to something new, a beginning again, a rebirth, a return to the one.

We know that Paterson struggles to express his emotions but manages to channel them through poetry. It is the way he opens himself to the world. Until he loses his notebook, the entire film unfolds in a monotonous state of pure presence or pure Da. We see this not only in the fact that Paterson writes his poems without acknowledging their importance, in contrast to Laura, who perceives their beauty and the need for him to share them. Paterson seems to inhabit a state of complete fullness. His routine on the way to work is the same, his routine at home is the same and his writing routine in the notebook is the same.

It is not until his dog destroys the notebook and leaves no trace of the poems that Paterson becomes aware of his loss, Fort. At that moment alterity or thirdness emerges, breaking the monotony of his life. This alterity also relates to Cheng’s notion of the void and to Peirce’s thirdness, brought back by Freud, in the sense that the structure of his life is disrupted and something linked to Law appears. His understanding of the world expands with this loss, just as the child at the end of the Oedipus Complex realizes that life is no longer binary, mother and child, but organized around a third term, the Father or Law, which will regulate life from that moment on and make relations with the world possible. This produced and necessary void is embodied in the empty notebook given to Paterson when the stranger notices, without many words, that he is an avid reader of poetry. It seems then that this void brings with it the thirdness or Law that is needed and that, as we noted, may well be represented by the Japanese man who gives Paterson the notebook. It opens the way to something new, a beginning again, a rebirth, a return to the one.

Film credits

Original title

Paterson

Year

2016

COUNTRY

United States

Director

Jim Jarmusch

Screenplay

Jim Jarmusch. Poems: Ron Padgett

Cast

Adam Driver, Golshifteh Farahani, Sterling Jerins, Luis Da Silva Jr., Frank Harts, William Jackson, Jorge Vega, Trevor Parham, Masatoshi Nagase, Owen Asztalos, Jaden Michael, Chasten Harmon, Brian McCarthy

Music

Sqürl

Cinematography

Frederick Elmes

Production companies

Prime Video, K5 Film, Le Pacte, Animal Kingdom, Inkjet Production Genre: Drama | Literature. Psychological drama. USA Independent Cinema

Distributor

Amazon Studios, in association with K5 International

Genre

Drama | Literature. Psychological drama. USA Independent Cinema

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

MORE

film reviews

Poor Things: Opening Minds

Poor Things: Opening Minds

Poor Things: Opening Minds

director

Yorgos Lanthimos

country

Ireland

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

Linger on (…) Perfect Days, by Wim Wenders

director

Wim Wenders

country

Japan

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

“El Jockey” and the Question of Being

director

Luis Ortega

country

Argentina

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.

© Topica Mag 2026.

© All images of their respective owners.